The way the faculty and students at EARTH University see it, there’s no excuse for not growing your own food. If their agricultural practices could catch on worldwide, many more people would be secure in their food supply ‚Äì a key Millennium Development Goal.

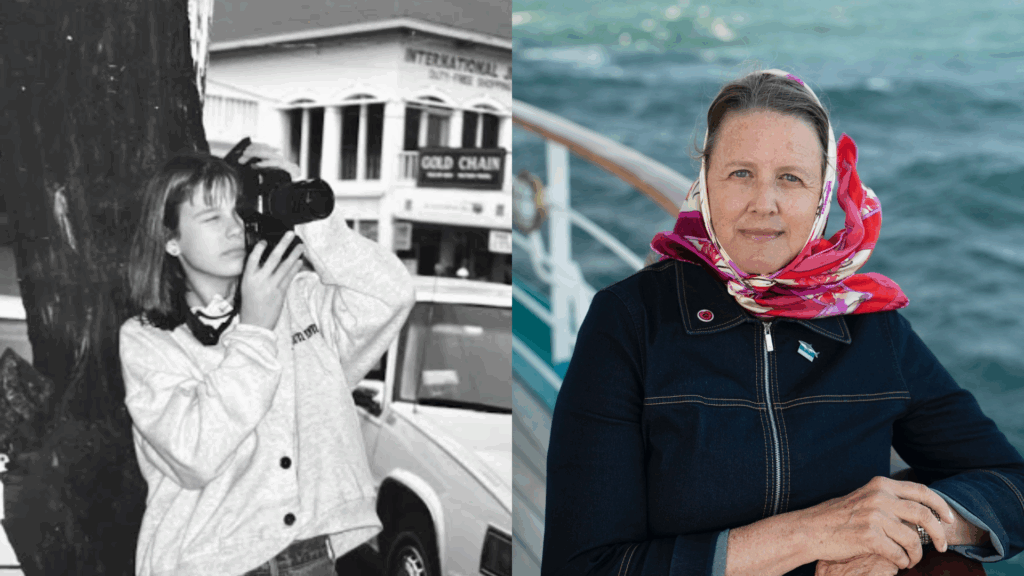

Students from Candice Shoemaker’s “Food Security and Food Production” class on the Maymester voyage of Semester at Sea visited planet EARTH during the MV Explorer’s three days in Costa Rica.

At EARTH – a Spanish acronym for the school of tropical agronomy and research – they learned how leafy greens, legumes, herbs and even tomatoes can be successfully grown in a hot and humid climate where the ground is unforgiving and the rain relentless.

The benefits go far beyond full bellies, said Alex Pacheco, a professor of natural resource management and one of 40 EARTH faculty members. Local foods help grow the local economy by providing extra income and saving money for families. “If you increase local production, you break a bit of the link to commercial systems,” he explained. A head of lettuce that costs a Costa Rican 300 colones ‚Äì about 65 cents ‚Äì in el mercado can be replaced by one that is homegrown, costing perhaps 180 colones.

On a micro scale, such sustainable agriculture practices could benefit individuals. In the larger picture, though, ending poverty and hunger will take global solutions. Shoemaker notes that the U.N. Millennium Development Goal of reducing by half poverty and food insecurity by 2015 won’t be met because of the worldwide recession and the demand for biofuels, which caused big increases in food prices.

“So the progress has actually gone down,” she said. “They’re projecting that they might be able to reach the goal by 2030.”

It’s not that we’re not producing enough food, Shoemaker said. Rather, it’s a question of availability, accessibility and sustainability. “All of those things are factoring into the mix as to whether there’s food insecurity,” she said.

The 400 students at EARTH, who come from 26 countries throughout the Caribbean, Latin America and Africa, spend four years learning not only about sustainable agriculture literally from the ground up, but also animal husbandry and entrepreneurship. Like all college students, they study, attend class and do research – and they also work the fields of the 8,000-acre campus. More than half of the food the students and faculty consume is produced at EARTH, right down el pollo in the cafeteria.

To be sustainable, agricultural practices must use free and locally available materials. The lettuce in Pacheco’s sustainable garden is growing in a raised bed of rice husks (usually burned for fuel), charcoal (from wood fires), and ground-up coconut shells. The planting mix stays dry on the top while roots ‚Äì not having to burrow into clay-hardened soil ‚Äì receive moisture from drip irrigation fed by gravity. This avoids the usual problem with leafy greens: fungus.

“To buy is forbidden,” said Pacheco, a native of Colombia. “We reuse everything: old shoes, tires, bottles‚Ķ” Raised beds in Pacheco’s garden are attractively ringed with two-liter plastic bottles and old tires.

Student Rachel Kenley, a member of Shoemaker’s class, noted that’s a hard sell for most Americans. “We’re trained to want the newest and the best.”

Pacheco said his program has three goals: “To have a garden that is beautiful, environmentally friendly and productive.”

Food plants are surrounded by herbs to repel insects. “Ornamental basil and coriander keep away insects,” Pacheco told the students. “We use chilis to attract insects so they don’t attack the plants. We repel and attract.”

He added, “It’s OK to use a fungicide, but if insect repellents kill insects, they kill us, too.”

This is no-excuses food production. Don’t have room for a garden? Go vertical. Pacheco and his students are growing tomatoes in hanging plastic bags. Can’t manage a big garden? Plant small. Pacheco demonstrated a planting container made from a plastic jug. Once planted, it’s light enough to move outdoors during the day and indoors at night ‚Äì even by a child or older person. Don’t have soil? Grow with hydroponics, starting with holes cut into a castoff sheet of Styrofoam that is then floated in water.

And it’s not just theory. Folks from surrounding communities come to EARTH for free instruction in these growing techniques. “When they finish, they start teaching other community members,” Pacheco said. “They can earn extra income plus food security.”

Student Laura VanderMause commented, “If everyone can produce a little for themselves, it takes the strain off big companies to have to produce for everyone.” Classmate Sydney Tenhundfeld added, “It’s a neat idea for a minimum-wage family to grow a few vegetables so they can feed themselves without spending money. They don’t even have to drive to town, so they save on gas.”

Shoemaker said she is impressed with the work EARTH is doing. “We got a nice overview of different ways we can grow food depending on what the situation is in terms of food security,” she said. But that alone won’t end poverty and hunger.

“At the government level, one strategy would be to target poverty, if it’s education or developing employment opportunities,” she said. “At the global level, we look more at food policies and trade policies.” For example, she said, local farmers can’t compete with the price of U.S.-government subsidized imported grain. Local production, she said, has to be balanced with imports.

“That’s the global challenge of trying to even out the playing field,” she said.