Sometimes called the “rice bowl of Vietnam,” the Mekong River and Mekong Delta have served as a source for food and livelihood in Southeast Asia for centuries. Traditionally, local farmers have grown rice in Mekong Delta, benefiting from annual monsoon floods to fill the paddies and a dependable market to sell their crops after harvest, but the pressures of globalization and economic development have strained farmers in the region, causing them to explore alternative forms of income.

Enter aquaculture. Starting in the 1990s, with an increased demand from the U.S. market and saltwater seeping up the Mekong River, farmers in the delta began to adopt shrimp and fish farming as new means of subsistence. Switching their rice paddies to shrimp farm ponds required farmers to destroy mangrove forests and pump fresh water from the aquifer to fill ponds.

“The impact of aquaculture in the Mekong Delta is a really complicated issue because it impacts people, local traditions, the environment, and the economy all at once,” said Professor Donna LeFebvre of UNC Chapel Hill. Among other issues, shrimp farming slowly increases the amount of salt water in the Mekong due to mangrove destruction, while intentional flooding of the ponds causes the already low-lying delta to sink into the ocean at a rate of several centimeters per year.

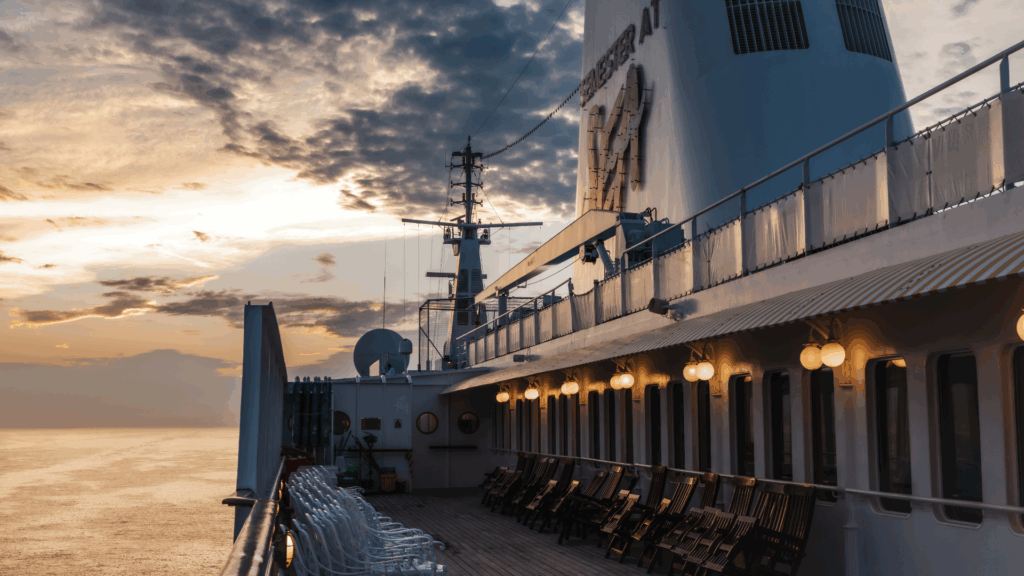

Following the shrimp boom, farmed fish also started to drive the local economy in the delta. Vietnam is the fourth largest aquaculture producer in the world, accounting for 3.8 million metric tons of farmed seafood annually. Floating fish farms pepper the Mekong River throughout the delta, a phenomenon Spring 2019 Voyagers enrolled in the political science course Globalization, Sustainability, and Justice explored during a recent field class.

The impact of floating fish farms is another challenge facing the Mekong River delta because farmers use hormones and fertilizers to grow the fish faster than the normal growth rate, polluting the water, which then causes other farmers downstream to introduce even more external chemicals.

Students visited the floating fish farms of Mr. Be and Mr. Khoi on the Tien river tributary, where they saw how over 120 thousand tilapia, red snapper, bass, and catfish were farmed annually. Farmed fish can generate nearly $50,000/cage annually, which is a massive economic draw for farmers looking to improve their economic circumstances.

“Seeing the fish farms themselves was really impactful for me. In my head, the fish farms were these huge expansive things that cover the whole river but in actuality they are these floating houses with small nets that are jammed with fish,” said Ben Wagner from the College of William and Mary. “I think being able to read something and then shift it to the reality is a really important component of field classes.”

Following the tour of the fish farms, students headed over to the U.S. Consulate in central Ho Chi Minh City to meet with Joanie Bartholomaus, an economic officer stationed in Vietnam. Joanie spoke with the students about the threats facing the Mekong, describing it as a “potential slow moving disaster that doesn’t seem to have a viable environmental or economic solution.” She explained how in developing countries like Vietnam, governments often prioritize increasing the size of the middle class and growing the economy over sustainability or environmental justice, which can account for issues like the ones facing the Mekong.

Everett Bossard from Troy State University said “Joanie broke down parts of the Mekong Delta issues, which is a really complicated topic, and simplified it in a way that made it easier for me to understand. It was interesting to hear how someone at the U.S. State Department, which can’t really do anything about the issue, works on how this might affect U.S. interests.”

Connecting the dots between what students saw at the during their field class and what they’ve been studying in on-ship, students were able to synthesize the challenges faced local Vietnamese communities and how it affects economies and people around the world.

“The most impactful part of the day for me was talking to [Joanie} because she was able to integrate all kinds of themes that we’ve been covering in class from an expert’s point of view,” said Sarah Franklin from University of Virginia. “She is able to look at data and statistics about what is going on and can see the big picture.”