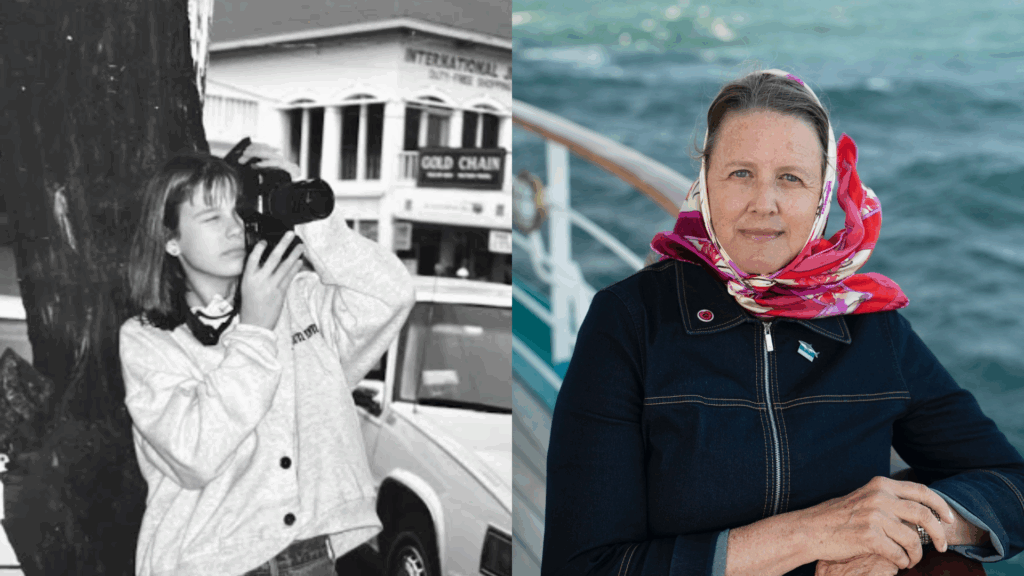

Written by a faculty member, Colleen Cohen.

We were due to dock in the Hawaiian Islands at 6 a.m. on January 12, so yesterday morning I went up to the bow of the ship at about 5 a.m. to watch us come in. We were still ways out, and it was dark, but the silhouette of Diamond Head stood out dramatically against the lights of Waikiki. Several students had slept out on the deck during the night in order not to miss our arrival, but they were still asleep and so were, basically, missing it. They managed to rouse themselves before we pulled into the harbor, but by that time Diamond Head was behind us, with the skyscrapers of Waikiki looming over the port.

We were due to dock in the Hawaiian Islands at 6 a.m. on January 12, so yesterday morning I went up to the bow of the ship at about 5 a.m. to watch us come in. We were still ways out, and it was dark, but the silhouette of Diamond Head stood out dramatically against the lights of Waikiki. Several students had slept out on the deck during the night in order not to miss our arrival, but they were still asleep and so were, basically, missing it. They managed to rouse themselves before we pulled into the harbor, but by that time Diamond Head was behind us, with the skyscrapers of Waikiki looming over the port.

Today was the day of my first field lab. Every class that Semester at Sea students enroll in has a field lab associated with it. These labs are all-day sessions with activities meant to augment the focus of the course. My lab was done in conjunction with my Anthropology of Tourism course, and the focus was on the growing emphasis in Hawaiian tourism on the “host” experience rather than the “guest” experience. What this means, according to our guide Monte McComber, from the Native Hawaiian Hospitality Association, is that whereas the initial focus of Hawaiian tourism was in making sure that Western tourists would see the Hawaii that they imagined (the Hawaii of tropical beaches, luaus, beach boys and surfboards), since the 1980s there has been a push to educate tourists about the things that are important to Hawaiian natives.

The first part of our lab experience was a walk along the entire stretch of Waikiki, making note not of key tourist sites but rather of the location of old fish ponds, the place where two streams used to converge, the place where famous Hawaiian surfer Duke Kanahamoku had his Hui Nalu surf club, for example.

Much as we tried to imagine a Waikiki before tourism, during this walk we were constantly pulled back into the reality of today by souvenir stores, chain stores, and chain restaurants on every corner, and other kitsch of contemporary Hawaiian tourism. Nonetheless, when we got to the Royal Hawaiian court, we did manage to step back in time a bit.

Much as we tried to imagine a Waikiki before tourism, during this walk we were constantly pulled back into the reality of today by souvenir stores, chain stores, and chain restaurants on every corner, and other kitsch of contemporary Hawaiian tourism. Nonetheless, when we got to the Royal Hawaiian court, we did manage to step back in time a bit.

The land on which the Royal Hawaiian court sits was owned by Princess Pau ªahi, the great-granddaughter of King Kamehameha I, the monarch who in 1810 unified all the islands of Hawaii as one kingdom. Upon Princess Pau ªahi’s death, her land was held in trust, and to this day, it is stipulated that a quarter of every square foot of rental income of buildings that sit on the land be put toward cultural programming. The court itself is a cool quiet grove away from the noise and bustle of Waikiki beach, and, as our guide pointed out to us, it is very, very valuable real estate, and as such, a powerful symbolic reminder of the importance of Hawaiian culture. Off the grove, itself are venues for cultural programming ‚Äì from lei-making for tourists to cultural events for school children and Native Hawaiian groups.

From Waikiki, we went to Iolani Palace, the palace of King David Kalakaua and Queen Lill’uokalani. Besides being the only Palace of a royal family in the entire United States, the Iolani is also a reminder of the grandeur of Hawaii’s past. The Throne Room alone is a testament to the legitimacy of the nation that was taken over by a handful of planters who felt that the native people were incapable of ruling over a modern nation and economy. Ironically (or perhaps not so much) in the 1970s there was a move to tear down the palace to make room for a parking lot. Fortunately, Hawaiians of all backgrounds fought this, and the Palace still stands.

We followed up our visit to Iolani Palace with a visit to Hanaiakamalama, the summer residence of King Kamehameha IV and his wife Emma. Here, again, we got a rich sense of the history of the Hawaiian monarchy, through such disparate items as the feather cape of King Kamehameha I and the sterling silver christening vessel that was given to Kamehameha IV and his wife by Queen Victoria, who was the godmother to their son, Nicholas. Hanaiakamalama is overseen by the Daughters of Hawaii, a group founded in 1903 with the intent of bringing women of Hawaiian ancestry together for the purpose of preserving Hawaiian language, history and culture. As interesting as Hanaiakamalama was, it was also interesting to hear the life stories of the docents who led us on our tour ‚Äì both of them with ancestry that traces to before Captain Cook’s arrival in 1778, but also with a mixture of multiple other ancestries.

By the time we finished at Hanaiakamalama, it was getting late ‚Äì too late to pay a visit to the place where all the monarchs are buried. So we made a short stop instead at a small shopping mall, in order to give the students an opportunity to witness yet another “tourist” space. There, they saw shops such as The Hawaiian Cookie Factory and a Hawaiian craft shop, and eateries such as Hawaii Dog and Hawaii Barbeque. But these were the exceptions. Most of the shops were generic “tropical wear” shops with, as one of my students noted, “lots of stuff from Indonesia and India.” And alongside Hawaii Barbeque in the food court was a sushi place, a Korean Barbeque, an egg roll place and a Subway! An interesting and illuminating contrast to the historical Hawaii we had been visiting all day.

On our way to the shopping mall, Monte engaged us in some musical “sharing,” having us sing along with him to some Hawaiian music that one might hear at a typical Hawaiian tourist show. The hands-down crowd favorite in this genre was the Hukilau Song, which included hand gestures for throwing nets, eating at a luau, swimming fish, etc. As raucous as the bus was during the singing of Hukilau (with its chorus, “Oh we’re going to a hukilau/A huki huki huki, huki, hukilau”), we all became silent and contemplative as Monte sang the ballad-like Kaulana Na Pua, with its final stanzas.