With many on board having strong European familial ties, the Fall 2014 faculty and students had the unique opportunity to trace their origins throughout their Atlantic Voyage. With the ship starting its journey in Europe, World War I and II history was prevalent in many port cities and surrounding areas. It was in Belgium that a faculty member and her family were able to find her mother’s childhood home where she hid during a Nazi invasion.

As the ship docked in Belgium, Professor Michelle Kisliuk and her family traveled to Brussels to find a link to their heritage. Her mother, born in 1930, grew up as a Jewish child in Vienna until she escaped with her family to Brussels when Adolf Hitler’s motorcade entered their hometown. Not long after her relocation, she learned that Brussels too was not safe for the Jewish population.

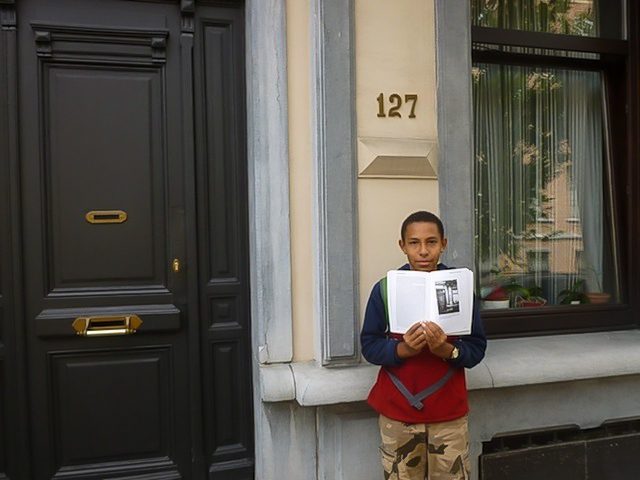

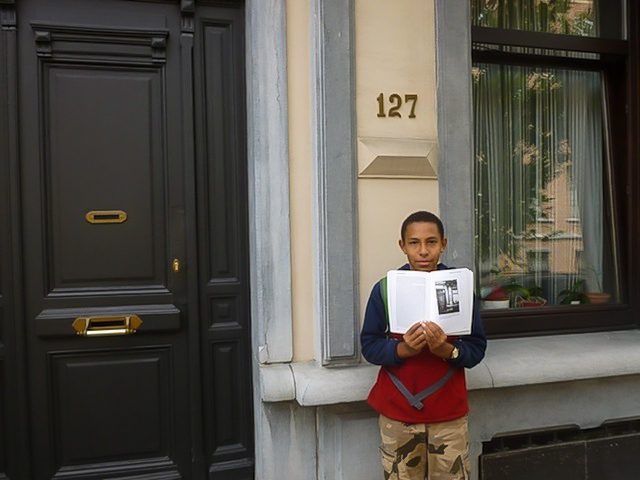

Upon a home invasion by the Nazi’s, Kisliuk’s grandmother hid her mother, uncle, grandfather and herself in dressers and armoires in their apartment’s basement. Disconnecting the light bulb and leaving each piece of furniture propped open to stage the space as if they had already left, her grandmother and family were able to avoid Nazi capture. Soldiers peered into the basement with flashlights and stood right in the same spot that Kisliuk and her family explored during their visit. “It was very eerie yet important to be in that basement. I could sense where the cabinets had been and where they had hid,” said Kisliuk. Sitting silent and terrified in the space, her mother recalled hearing screams from the streets as 200 families from the area were forced out by the Nazis. “I’ve always thought of my grandma as quiet. I knew what she went through, but it was really important for me to see it,” said Kisliuk’s 12 year-old son, Max Mongosso.

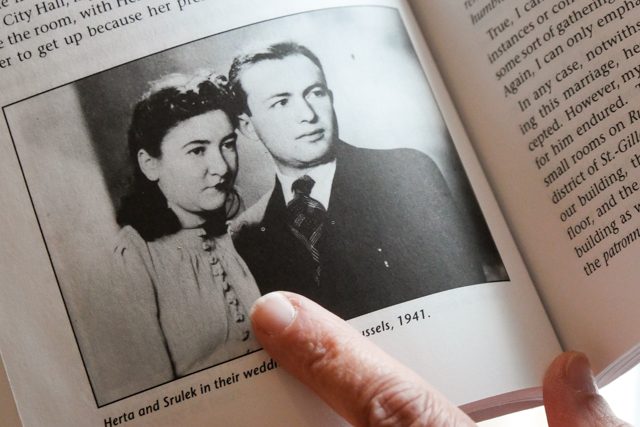

While this was a big part of their family’s past, it was not until her mother was in her 70s that she could really share these experiences. Preserved in a memoir, her story of survival shows the strength, ingenuity, and luck her family had during World War II. “As we grow older, what we thought as children was basically ancient history (the early 1940s) was in fact very recent, and this reality was brought thoroughly home by being present in the space and seeing such things as the light fixture where my grandmother had brilliantly removed the light bulb as they scrambled to hide,” added Kisliuk.

Losing an aunt in Auschwitz and numerous relatives throughout the war, their family’s exposure to Jewish struggles and adversity during World War II has been in depth. Over the course of their lives they have encouraged their mother to connect with other hidden children and process her experiences with those who survived the same strife. “I’ve heard hundreds of (Holocaust) stories and each one is the worst story you’ve ever heard,” said Kisliuk’s sister, Claudette Beit-Aharon. But for Kisliuk’s son Max, this experience served as a window into their family’s past and a direct connection to international history.

With France as their next destination, the sisters thought there was one more stop needed to complete Max’s World War II education‚Äìthe D Day Beaches in Normandy. As they walked the beach and watched a ceremony in the American cemetery, they could not help but draw a connection to their pilgrimage in Brussels. “Whenever I would goof around during the pledge of allegiance I would get this look from my grandma. Now I understood why,” said Max. Grateful for the Allies assistance in ending the war, they looked around at the sacrifices that were made right in that very spot. “Because they suffered and died I’m alive. We owe them our lives. Because of their bravery I am alive,” remarked Beit-Aharon.

Photos by: Joshua Gates Weisberg