Friday, May 26th, 9 am. 13 students, one professor and one reporter boarded a bus headed for a day of hands-on geology as part of the Geology of Central America class. Their day took them from rocky peaks more than 1000 feet above Peru to sea level directly above a fault. What follows is what this team discovered on their geological exploration.

Every class on the Short Term 2012 voyage of Semester at Sea includes a field lab requirement. One day in one port, the entire class spends a day in the field doing examining topics relevant to their course work. In the case of Geology of Central America, taught by Professor Skokan of the Colorado School of Mines, this means exploring some geologically interesting parts of Lima, Peru. We happen to be in South America, not Central America, but Peru is highly geologically interesting. Minerals are one of their top exports and the geography lends to very diverse landscapes and rich mines.

The immaculately clean bus we're riding in contrasts ramshackle huts as we wind our way up dirt roads to one of the highest parts of Lima, an area as geologically rich as it is tall. It is also historically important, with the site of a battle that took place in 1881 between the Peruvian army and the Chilean army.

The bus drops us off at the site and we meet a mining engineer from the Pontifical Catholic University of Lima, Peruvian Geologist Mario Cadron. Cadron and Professor Skokan will be our guides for the rest of the day, teaching us about Peruvian geology in a way that couldn't possibly be learned from a book or a lecture. “We're looking at the beach deposits and the shore deposits. We're going to learn about all these rocks and examine some environmental protection issues,” Professor Skokan says before adding that she is “incredibly glad that the students have the opportunity to get out of the class and participate in some real geology.”

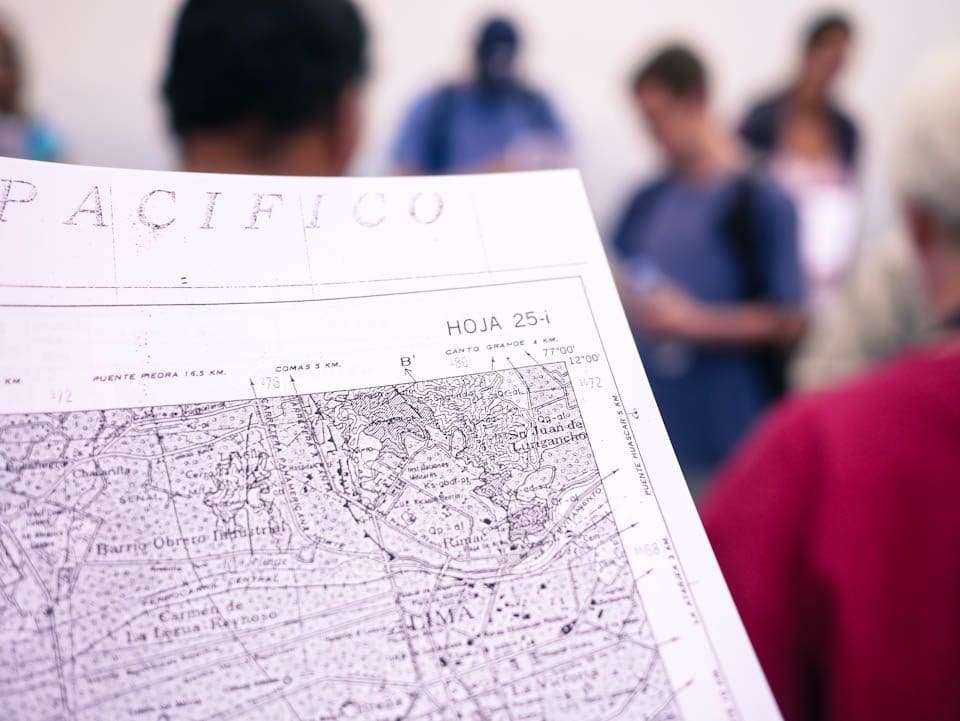

As Cadron introduces himself and his team, he passes out photocopied maps covered in Peruvian geological information, all labeled in Spanish. Some of the students speak Spanish, but the ones that don't are able to use the language of geology to decipher the information they need for what we're about to do. “We look at these rocks on Google images, but to see it in person is pretty incredible,” says University of Wisconsin Milwaukee student Matt Haley. Haley is a marketing major but fits in effortlessly with the mostly science majors he finds himself surrounded by. As fog rolls in from the Pacific Ocean we've got the entirety of Peru on one side of us and dramatic cliffs down to the sea on the other. It's breathtaking and unlike any classroom students have been in before. The coast of Peru is a desert, but not in the sense that we are familiar with deserts. It's humid and foggy. If not for the landscape, it feels like we could be in San Francisco.

Cadron is a constant stream of information as our group tentatively makes its way down the mountain. “We have earthquakes every day, but they're usually so small we don't feel them,” he explains as he points out a distant split in the hillside that came from a larger quake. It wouldn't be until a few hours later that Cadron would let us in on the fact that our entire field lab has taken place directly on top of a fault. Whether it was active or not, he couldn't or wouldn't say. Cadron is gregarious and funny as he teaches us about geology. He is as quick with a smile and a joke as he is with his rock hammer.

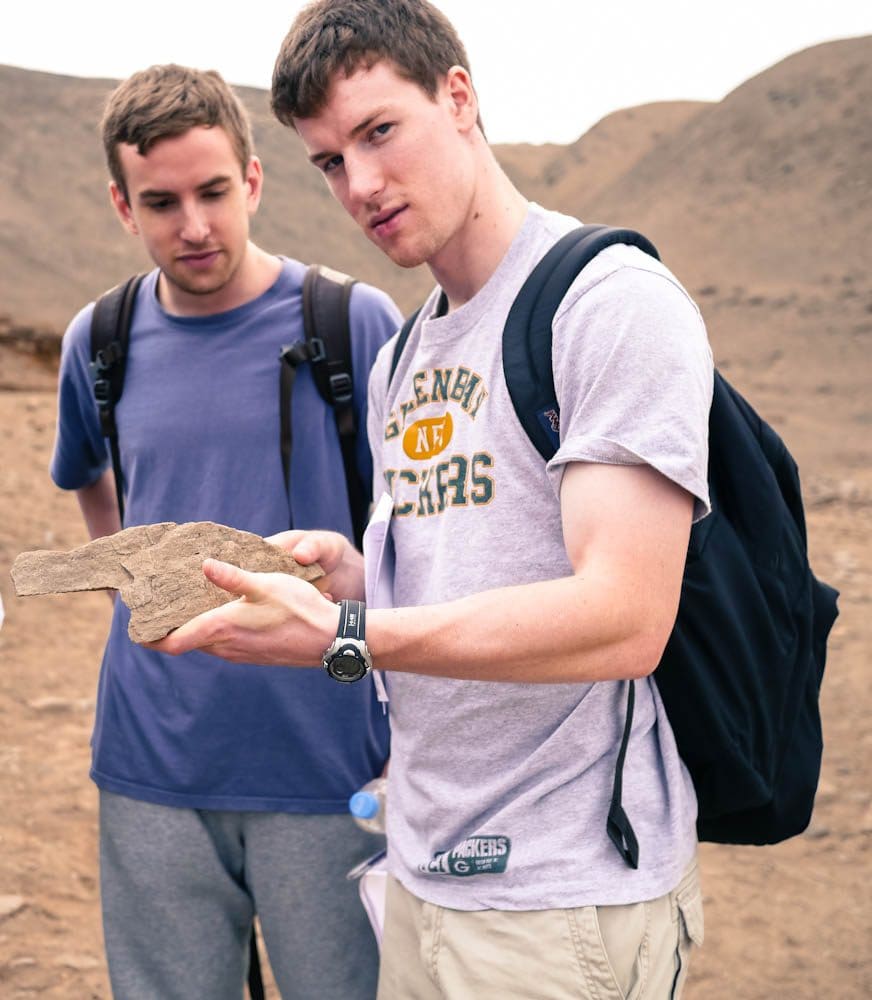

As we play mountain goat, or perhaps more appropriately mountain Alpaca and make our way down the cliff, the story begins to unfold that much of the rock we're surrounded by is limestone. Cadron chips off limestone specimens and passes them around to the students. “15% of our national gross is from mining. We live on mining,” he explains. Each student thoughtfully examines it before writing down a few notes and perhaps snapping a photo. Maps come out of pockets and coordinates are noted. Students will be writing a field report about today as an assignment and don't want to lose any of the relevant details. Skokan fills in information when necessary but mostly sits back and smiles proudly at her curious students. After just four days of class, they know their geology well enough to be fascinated by the opportunity they currently find themselves in. “We've spent the first few days studying land forms and mining conditions,” Skokan mentions.

“We learned about ninety degree cleaves, but to see it like this…it's so much clearer than it could be in a picture or a textbook,” University of Virginia student Emily McDaniel explained in excitement.

Eventually we made it to the bottom of the peak where the fault mets the Pacific Ocean and was most apparent. As we were making our way down, Cadron had mentioned the story about a monk who committed suicide by diving off the cliff above the fault. To honor this, a monk dives off a (much shorter) cliff into the ocean every day at a specific time. Serendipitously, our group had made it to the bottom of the hike at the perfect time to watch the monk jump. He had a definite flair for the dramatic as he jumped and waved from across the water. After several minutes of buildup, he plunged from the safety of land into the cold, dark sea. In spite of themselves, the students let out an audible gasp as he fell, before popping up safely and beginning his swim back to the beach just seconds later.

It was a majestic performance and neatly tied some Peruvian culture and folklore into the geologic features we had been studying all day. It perfectly punctuated our unique day in the field learning about the geology of Lima, Peru.