Students, Staculty, and Lifelong Learners onboard the Spring 2017 Voyage competed in a storytelling contest, all trying to answer the question, “What is a traveler?” On April 7, voyagers had the chance to read aloud their pieces to their fellow travelers and a panel of judges, who voted for the top selections. Read the winning piece below!

Contest Winner:

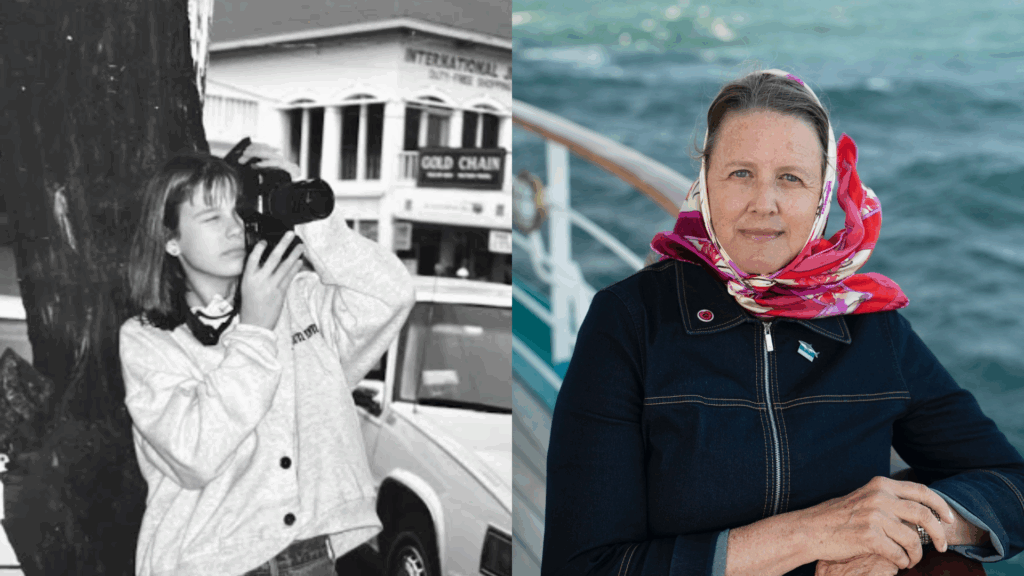

Cameron Hahn goes to Elon University where she is a double major in arts administration and strategic communications, with a double minor in business and theatre. She lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina, where she and her family are home to both a horse rescue and an Australian shepherd puppy rescue. Her farm also used to be home to six peacocks that continually escape the farm next door to run around her lawn. She has spent her past summers working several internships in casting for theatre and film, and was excited to be hired to cast her first movie last summer. For now, she spends most of her time either taking a nap or trying to act casual as she sits alone at a table for seven in Berlin and waits for her friends to show up to six-on-six. She would like to congratulate all of the other finalists on their absolutely incredible stories.

Hahn’s Submission:

When it was over, the duke’s nephew had kissed her. Later on, no one would remember this, because no one at the funeral knew, and because the nephew too had long forgotten the kiss. Young men, everywhere, seem to have memories like butter in griddles, sliding about and melting and always disappearing. A duke’s nephew, used to the constant flow of ladies attracted to his status and charm, was no exception.

But the violinist remembered. The violinist had seen the kiss, because the duke’s nephew and the girl were in the top box above stage right, and the violinist was only second chair, so he didn’t get to sit center stage under the brightest spotlights like the first chair did. This was something he was typically a little bitter about. But if he had been sitting center stage that night, the beams would have been too bright and entirely shaded his view of the audience, and so as the elegy concluded, the violinist wouldn’t have set down his violin to hear the piano play out, and he wouldn’t have seen the duke’s nephew lean in to her, catching her by surprise, and witnessed her dark hair become entangled in his hand as he pulled her close.

The memory startled her out of the pew she was sitting in. It was √âl√©gie Op. 24, the same sonata that had played that night in Paris at the Opera Garnier, that had plunged her into her reverie in the first place: how curious that the same elegy was being used for the funeral. Surely, she thought no one could have known of the song’s significance; no one knew about that night with the nephew, let alone about the kiss. She had been looking at the violinist before the nephew blocked her view, and she had seen that he was looking at her, and so, maybe, she thought, maybe he knew about it. But the opera box had once been exclusively for members of the royal family and their guests, nowadays reserved for those of the old noble French circles who clung to their lineages like ivy on crumbling brick; so surely the violinist had been privy to the flirtations of the French elite for the entirety of his career at the Garnier. What was one little secret between an operatic violinist and a young foreign biologist, fresh out of high school?

What was for sure was that none of her family or friends knew. From the moment her plane touched down on the boiling tarmac in her small dusty hometown airport, she sealed those memories up in her mental sarcophagus. It really was just a matter of believability: rainy, romantic Paris evenings at the symphony with the sons of the old monarchy were such an unfathomable reality to her loved ones that it was better to savor the memory just for herself. She knew it would be disappointing if she tried to explain it to her family or friends; she had never been very good with words, especially when it came to describing her travels, and her frustration at not being able to express her experiences would overpower the memoirs and sour them. So she let the most special memories be her own and they glowed in her; lightning bugs in a mason jar, tucked close to her heart.

At the funeral, at that moment, the mood in the room shifted. The whole somber affair had already been gloomy enough, but now the air became heavier, thicker, with the congregation feeling their lungs compress and constrict, as if they were trying to run a marathon in Beijing smog. It swept up the aisle, stopping each person’s breath in their tracks as they saw the facial expression of the woman who was being helped into the room ,

The mother was entering.

A man with dark brown hair escorted her. Its dark russet lowlights and untamable curl were identical to that of the girl in the pew, and she twisted a lock of hers around her finger, fondly realizing the likeness all over again for the millionth time. The girl watched the mother crumple into a pew across from her, and remembered the day the news came.

The mother had been at the kitchen sink, washing the garden vegetables for caprese, one of the man’s summer favorites. The man was at work still, but she was expecting him home soon. The phone rang, and her hands were wet with the half-washed tomatoes, so she let it go to the answering machine. Then it rang again, and the mother sighed and dried off her hands on her t-shirt and picked up the receiver.

When the girl had left, she had buried the mother in so many assurances that everything would be fine. She left her behind with promises and a yellow bedroom, which had become an untouched shrine to daughters lost since the call came. But the girl had always been gone, really. She was gone at seven years old, as she sat inches away from her mother who was brushing her hair into ribbons, reading the coffee table book full of pictures of faraway places. She was gone at 15, the day her best friend got her license, feeling her baby feathers grow into wings as she flew over the dirt roads of her tiny town, with the wind in her ears whispering that if she closed her eyes, she could be in the Sahara, with desert sand and not the dust of the American Midwest kicking up behind her. And she was gone the day after college graduation when she left for Brazil, the suitcase her mother packed full of pills and potions for any medical malady in tow.

At the end of high school, gap toothed and gap yeared, the girl had gone abroad for the first time and never got the taste out of her mouth. She had darted around Europe and Africa, and learned the secret of any traveler who wanted to really have the time of their life: itinerary planning was for breakfast of the day of.

But in the grief of everyone in the church, the girl in the pew didn’t see Europe or Africa. She saw the 4x4s of Jericoacoara. Jericoacoara was why she had left home in the first place; she walked off the commencement stage and onto her flight, diploma still in hand, on a full research scholarship to study Brazil’s bioluminescent phytoplankton and the opportunities their light-emitting enzyme, luciferase, posed for further deep sea study. Jericoacoara, despite being a bumpy, jungly 5-hour ride from the nearest town in the back of a 4×4, was idyllic; no cell service, no TV, and sometimes not even money. Just the Sunday edition of O Globo and a primitive email system that allowed encrypted messages to be sent back to southern California with the luciferase’s research updates. The village was so far out that the only way to get there was in the back of a 4×4; but so often, they would spin their wheels in place, revving through jungle roads that simply insisted on swallowing the vehicle’s axles whole. Locals were used to dropping their work at a moment’s notice to help whoever was in need of a rescue. Once, on her earlier trips out to the remote research station, an American guide had joked the real saying should be that it takes a village to raise a car out of a sinkhole.

Unlike the 4×4, grief had put the mother in the rut permanently. Right now, everyone was showing up to help wrench her out of it, bringing casseroles in the place of ropes and offering cardstock sympathies instead of hollering to pull on the count of three. But grief and jungles take what they want and leave only skeletons of the people who have gone through them behind.

In Jeri, as she came to call her South American village, she found Atlantis in the magic of the nighttime’s glowing purple beaches, full of luminescent ocean animals. The way the station’s kind house lady, Tehangua, beamed at her with a machete swinging on her apron for hacking open coconuts at a moment’s request reminded her of her own mother’s smile, and she felt at home in the middle of a world alien from the one she grew up in. The markets, the fruit, the flora and fauna and feeling of bold Brazilian flavor hypnotized the girl. But the bioluminescence and its brilliant nightly display of the northern lights on sand was why she stayed.

At the end of her twenty-fourth year, she caught the attention of the global biological community when her luciferase findings were published by Harvard Printing; a single phone call from David Tilman, and she was boarding a plane to Japan to present to the Society for the Promotion of Science.

All those pills, and all those potions, packed so carefully by her mother in her suitcase. None of them prevent explosive decompression from a Boeing 747’s with a weak aft pressure bulkhead. A week after her twenty-fifth birthday, she was flying for the last time, careening towards Earth at an uncontrollable speed. They were some of the lucky ones, the rescuers later told her family, in the midst of the noise the throngs of media created; her body was intact. It was smoke inhalation that had quietly put out the genius girl, the pride of a town that didn’t understand her yet heralded her brains and brave.

She had lived a million lives in twenty-five years, and she wasn’t sad. It did feel weird to be the only one at a funeral who wasn’t sad, the girl in the pew thought; while everyone was feeling guilt for the things they didn’t say to the girl dead, she felt only guilt that she didn’t miss the girl alive.

The elegy was nearing its crescendo now, and she could feel, somehow, that there wasn’t much time left. She sighed, not unhappily, and stood up from her pew. No one took notice of her, as if no one had noticed her sitting there at all in the first place. Which they hadn’t. People were so blind to everything. She used to be blind herself, but her optometrist was books and her prescription was frequent flyer miles.

So lightly she went across the church carpet, past the mother, past the mourners, past the man, past neighbors and her old babysitter and her mother’s coworkers and her middle school lunch-lady and her sophomore year crush and her grad school ichthyology professor, past everything she knew and past the girl in the purple-lined coffin with the stiff hands and the bland dress and the hair that had been wrestled into submission from its standard mane of gnarled curls that had felt the winds of six continents.

Glancing away from herself in the coffin, she turned to the assembly, and looked upon all these people she loved. She had always had wings – all travelers had wings – and so wasn’t it fitting that she should die young and get to use those wings like an actual angel? But these people here around her ‚Äì they were the ones who had taken the shears to their own feathers, clipped them one by one with each day they stayed confined to their own tiny towns, and never thought of the world swirling around them. She was the only who had lived in a room full of the living.

The girl thought inexplicably of the violinist, and it made her happy to think of how many other silly couples he would play for, and she stepped into the winds of providence that had taught her to fly. And she wasn’t afraid, and she laughed when she felt it gather up around her, swirling through her fingertips and toes and her hair, and she was traveling to the next, and she was gone.